How Did Sailors Repair Sails In 1906

Full-rigged ship

Barque

Barquentine

Schooner

Showing three-masted examples, progressing from square sails on each to all fore-and-aft sails on each.

A sailing send is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the ability of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships carry square sails on each mast—the brig and full-rigged ship, said to exist "ship-rigged" when in that location are iii or more masts.[i] Others carry just fore-and-aft sails on each mast, for case some schooners. Even so others employ a combination of square and fore-and-aft sails, including the barque, barquentine, and brigantine.[two]

Early sailing ships were used for river and littoral waters in Ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean. Blue h2o ocean-going sailing ships were outset independently invented by the Austronesian peoples with the fore-and-aft crab-claw canvas also every bit the culturally unique catamaran and outrigger boat technologies. These enabled the rapid Austronesian expansion into the islands of the Indo-Pacific since 3000 BC from an origin in Taiwan, besides as facilitated the first maritime trading network in the Indo-Pacific from at to the lowest degree 1500 BC.[3] [4] Later developments in Asia produced the junk and dhow—vessels that incorporated innovations absent in European ships of the time.

European sailing ships with predominantly foursquare rigs became prevalent during the Age of Discovery, when they crossed oceans between continents and around the world. In the European Age of Sail, a total-rigged ship was one with a bowsprit and three masts, each of which consists of a lower, superlative, and topgallant mast.[five] Nearly sailing ships were merchantmen, merely the Age of Sail also saw the evolution of big fleets of well-armed warships. The Historic period of Sheet waned with the advent of steam-powered ships, which did not depend upon a favourable wind.

History [edit]

The outset sailing vessels were adult for use in the Southward China Sea by the Austronesian peoples, and also independently in lands abutting the western Mediterranean Sea by the 2nd millennium BC. In Asia, early on vessels were equipped with crab hook sails—with a spar on the top and bottom of the sail, arranged fore-and-aft when needed. In the Mediterranean, vessels were powered downwind by foursquare sails that supplemented propulsion by oars. Sailing ships evolved differently in the Due south China Sea and in the Indian Ocean, where fore-and-aft canvass plans were developed into several centuries Advertizing.

Past the time of the Age of Discovery—starting in the 15th century—foursquare-rigged, multi-masted vessels were the norm and were guided by navigation techniques that included the magnetic compass and making sightings of the sun and stars that immune transoceanic voyages. The Age of Sail reached its meridian in the 18th and 19th centuries with big, heavily armed battleships and merchant sailing ships.

Sailing and steam ships coexisted for much of the 19th century. The steamers of the early on part of the century had very poor fuel efficiency and were suitable simply for a minor number of roles, such as towing sailing ships and providing short route passenger and mail services. Both sailing and steam ships saw large technological improvements over the century. Ultimately the two large stepwise improvements in fuel efficiency of chemical compound and and then triple-expansion steam engines made the steamship, by the 1880s, able to compete in the vast majority of trades. Commercial sail nevertheless continued into the 20th century, with the last ceasing to trade past c 1960.[6] : 106–111 [7] : 89

Before 1700 [edit]

Initially sails provided supplementary power to ships with oars, because the sails were non designed to sheet to windward. In the Austronesian Indo-Pacific, sailing ships were equipped with fore-and-aft rigs that made sailing to windward possible. Later foursquare-rigged vessels also were able to sail to windward, and became the standard for European ships through the Age of Discovery when vessels ventured around Africa to Bharat, to the Americas and effectually the globe. Later during this catamenia—in the late 15th century—"ship-rigged" vessels with multiple square sails on each mast appeared and became common for sailing ships.[8]

Mediterranean and Baltic [edit]

Roman warship with sails, oars, and a steering oar

Sailing ships in the Mediterranean region date dorsum to at least 3000 BC, when Egyptians used a bipod mast to support a single square sail on a vessel that mainly relied on multiple paddlers. Later the mast became a single pole, and paddles were supplanted with oars. Such vessels plied both the Nile and the Mediterranean coast. The Minoan culture of Crete may have been the world'southward kickoff thalassocracy brought to prominence by sailing vessels dating to before 1800 BC (Middle Minoan IIB).[9] Betwixt 1000 BC and 400 Advertisement, the Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans adult ships that were powered past square sails, sometimes with oars to supplement their capabilities. Such vessels used a steering oar as a rudder to control management. Fore-and-aft sails started actualization on sailing vessels in the Mediterranean ca.1200 AD,[eight] an influence of rigs introduced in Asia and the Indian Bounding main.[ten]

Starting in the 8th century in Denmark, Vikings were edifice dissidence-constructed longships propelled past a single, square canvass, when practical, and oars, when necessary.[11] A related arts and crafts was the knarr, which plied the Baltic and Due north Seas, using primarily sail power.[12] The windward edge of the canvass was stiffened with a beitass, a pole that fitted into the lower corner of the canvas, when sailing close to the wind.[thirteen]

South Prc Sea & Austronesia [edit]

Chinese junk Keying with a center-mounted rudder postal service, c. 1848

The commencement sea-going sailing ships in human being history were developed by the Austronesian peoples from what is now Taiwan. Their invention of catamarans, outriggers, and crab claw sails enabled the Austronesian Expansion at around 3000 to 1500 BC. From Taiwan, they rapidly colonized the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia, then sailed farther onwards to Federated states of micronesia, Isle Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. Austronesian rigs were distinctive in that they had spars supporting both the upper and lower edges of the sails (and sometimes in betwixt), in contrast to western rigs which only had a spar on the upper border.[three] [fourteen] [fifteen]

Early Austronesian sailors also influenced the evolution of sailing technologies in Sri Lanka and Southern India through the Austronesian maritime trade network of the Indian Ocean, the precursor to the spice trade road and the maritime silk road.[four] Austronesians established the offset maritime trade network with ocean-going merchant ships which plied the early merchandise routes from Southeast Asia from at to the lowest degree 1500 BC. They reached every bit far northeast as Nippon and every bit far west as eastern Africa. They colonized Madagascar and their merchandise routes were the precursors to the spice merchandise route and the maritime silk road. They mainly facilitated trade of goods from China and Japan to South India, Sri Lanka, the Western farsi Gulf, and the Reddish Bounding main.[4] [sixteen] [17] An important invention in this region was the fore-and-aft rig, which made sailing against the wind possible. Such sails may take originated at least several hundred years BC.[18] Remainder lugsails and tanja sails also originated from this region. Vessels with such sails explored and traded along the western coast of Africa. This type of sail propagated to the west and influenced Arab lateen designs.[18]

Large Austronesian trading ships with as many as iv sails were recorded past Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 Ad) scholars as the kunlun bo (崑崙舶, lit. "transport of the Kunlun people"). They were booked by Chinese Buddhist pilgrims for passage to Southern India and Sri Lanka.[19] Bas reliefs of Sailendran and Srivijayan large merchant ships with diverse configurations of tanja sails and outriggers are also found in the Borobudur temple, dating dorsum to the 8th century CE.[twenty] [21]

By the tenth century AD, the Vocal Dynasty started edifice the first Chinese junks, which were adopted from the design of the Javanese djongs. The junk rig in particular, became associated with Chinese coast-hugging trading ships.[22] [23] Junks in China were constructed from teak with pegs and nails; they featured watertight compartments and acquired center-mounted tillers and rudders.[24] These ships became the basis for the evolution of Chinese warships during the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, and were used in the unsuccessful Mongol invasions of Nippon and Coffee.[23] [25]

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) saw the use of junks every bit long-altitude trading vessels. Chinese Admiral Zheng He reportedly sailed to India, Arabia, and southern Africa on a trade and embassy.[26] [27] Literary lore suggests that his largest vessel, the "Treasure Ship", measured 400 feet (120 m) in length and 150 feet (46 g) in width, whereas modern research suggests that it was unlikely to take exceeded 200 anxiety (61 grand) in length.[28]

Indian Sea [edit]

The Indian Ocean was the venue for increasing trade betwixt India and Africa betwixt 1200 and 1500. The vessels employed would be classified equally dhows with lateen rigs. During this interval such vessels grew in chapters from 100 to 400 tonnes. Dhows were oftentimes built with teak planks from India and Southeast Asia, sewn together with coconut husk fiber—no nails were employed. This period besides saw the implementation of centre-mounted rudders, controlled with a tiller.[29]

Global exploration [edit]

Technological advancements that were important to the Age of Discovery in the 15th century were the adoption of the magnetic compass and advances in ship design.

The compass was an addition to the ancient method of navigation based on sightings of the lord's day and stars. The compass was invented by Chinese. It had been used for navigation in Prc past the 11th century and was adopted by the Arab traders in the Indian Bounding main. The compass spread to Europe by the late twelfth or early 13th century.[10] Apply of the compass for navigation in the Indian Body of water was offset mentioned in 1232.[22] The Europeans used a "dry out" compass, with a needle on a pin. The compass menu was also a European invention.[22]

At the beginning of the 15th century, the carrack was the nigh capable European ocean-going ship. It was carvel-congenital and big enough to exist stable in heavy seas. Information technology was capable of carrying a large cargo and the provisions needed for very long voyages. Later carracks were foursquare-rigged on the foremast and mainmast and lateen-rigged on the mizzenmast. They had a high rounded stern with large aftcastle, forecastle and bowsprit at the stem. Equally the predecessor of the galleon, the carrack was one of the nearly influential ship designs in history; while ships became more than specialized in the following centuries, the basic design remained unchanged throughout this menses.[30]

Ships of this era were merely able to sail approximately 70° into the air current and tacked from i side to the other across the wind with difficulty, which made it challenging to avoid shipwrecks when well-nigh shores or shoals during storms.[31] Nevertheless, such vessels reached Bharat around Africa with Vasco da Gama,[32] the Americas with Christopher Columbus,[33] and effectually the earth nether Ferdinand Magellan.[34]

1700 to 1850 [edit]

1798 sea battle between a French and British man-of-war

The five-masted Preussen was the largest sailing send ever built.

Schooners became favored for some coast-wise commerce later 1850—they enabled a small coiffure to handle sails.

Sailing ships became longer and faster over time, with ship-rigged vessels conveying taller masts with more foursquare sails. Other sail plans emerged, also, that had but fore-and-aft sails (schooners), or a mixture of the ii (brigantines, barques and barquentines).[viii]

Warships [edit]

Cannon were present in the 14th century, but did not become mutual at sea until they could exist reloaded quickly enough to be reused in the same battle. The size of a ship required to carry a large number of cannon made oar-based propulsion incommunicable, and warships came to rely primarily on sails. The sailing man-of-state of war emerged during the 16th century.[35]

By the center of the 17th century, warships were carrying increasing numbers of cannon on 3 decks. Naval tactics evolved to bring each ship'due south firepower to bear in a line of battle—coordinated movements of a fleet of warships to engage a line of ships in the enemy fleet.[36] Carracks with a single cannon deck evolved into galleons with as many equally two full cannon decks,[37] which evolved into the man-of-war, and further into the send of the line—designed for engaging the enemy in a line of boxing. One side of a transport was expected to shoot broadsides against an enemy ship at close range.[36] In the 18th century, the small and fast frigate and sloop-of-state of war—besides small to stand in the line of battle—evolved to convoy trade, scout for enemy ships and blockade enemy coasts.[38]

Clippers [edit]

The term "clipper" started to exist used in the first quarter of the 19th century. It was applied to sailing vessels designed primarily for speed. Only a small proportion of sailing vessels could properly have the term applied to them.[7] : 33

Early examples were the schooners and brigantines, chosen Baltimore clippers, used for blockade running or equally privateers in the State of war of 1812 and later for smuggling opium or illegally transporting slaves. Larger clippers, ordinarily send or barque rigged and with a different hull design, were built for the California trade (from eastward coast United states ports to San Francisco) after gold was discovered in 1848 – the associated ship-building blast lasted until 1854.[39] : 7, nine, 13.14

Clippers were built for merchandise between the U.k. and China later on the East Republic of india Company lost its monopoly in 1834. The primary cargo was tea, and sailing ships, particularly tea clippers, dominated this long distance route until the evolution of fuel efficient steamships coincided with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.[40] : 9–10, 209

Other clippers worked on the Australian immigrant routes or, in smaller quantities, in any part where a fast passage secured higher rates of freight[a] or passenger fares. Whilst many clippers were send rigged, the definition is not limited to any rig.[39] : 10–11

Clippers were by and large built for a specific trade: those in the California trade had to withstand the seas of Cape Horn, whilst Tea Clippers were designed for the lighter and contrary winds of the China Ocean. All had fine lines,[b] with a well streamlined hull and carried a big sail surface area. To get the best of this, a skilled and determined principal was needed in command.[39] : 16–xix

Copper sheathing [edit]

During the Historic period of Canvas, ships' hulls were nether frequent attack past shipworm (which afflicted the structural forcefulness of timbers), and barnacles and various marine weeds (which affected transport speed).[41] Since before the common era, a variety of coatings had been applied to hulls to counter this issue, including pitch, wax, tar, oil, sulfur and arsenic.[42] In the mid 18th century copper sheathing was developed as a defense against such bottom fouling.[43] After coping with issues of galvanic deterioration of metal hull fasteners, sacrificial anodes were developed, which were designed to corrode, instead of the hull fasteners.[44] The practice became widespread on naval vessels, starting in the late 18th century,[45] and on merchant vessels, starting in the early 19th century, until the appearance of iron and steel hulls.[44]

After 1850 [edit]

Iron-hulled sailing ships, oftentimes referred to every bit "windjammers" or "alpine ships",[46] represented the final evolution of sailing ships at the cease of the Age of Sail. They were built to acquit bulk cargo for long distances in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were the largest of merchant sailing ships, with three to 5 masts and square sails, besides as other sheet plans. They carried lumber, guano, grain or ore between continents. Subsequently examples had steel hulls. Iron-hulled sailing ships were mainly built from the 1870s to 1900, when steamships began to outpace them economically, due to their power to keep a schedule regardless of the wind. Steel hulls too replaced iron hulls at around the same fourth dimension. Fifty-fifty into the twentieth century, sailing ships could agree their own on transoceanic voyages such as Australia to Europe, since they did not require bunkerage for coal nor fresh h2o for steam, and they were faster than the early steamers, which usually could barely make 8 knots (15 km/h).[47]

The four-masted, iron-hulled ship, introduced in 1875 with the full-rigged Canton of Peebles, represented an especially efficient configuration that prolonged the competitiveness of sail confronting steam in the later part of the 19th century.[48] The largest instance of such ships was the five-masted, total-rigged transport Preussen, which had a load capacity of 7,800 tonnes.[49] Ships transitioned from all sail to all steam-power from the mid 19th century into the 20th.[46] Five-masted Preussen used steam power for driving the winches, hoists and pumps, and could be manned by a crew of 48, compared with four-masted Kruzenshtern, which has a crew of 257.[50]

Coastal top-sail schooners with a coiffure as minor as two managing the canvass handling became an efficient way to carry bulk cargo, since just the fore-sails required tending while tacking and steam-driven mechanism was oftentimes bachelor for raising the sails and the anchor.[51]

In the 20th century, the DynaRig allowed central, automated command of all sails in a way that obviates the need for sending coiffure aloft. This was developed in the 1960s in Deutschland as a low-carbon footprint propulsion culling for commercial ships. The rig automatically sets and reefs sails; its mast rotates to align the sails with the wind. The sailing yachts Maltese Falcon and Blackness Pearl use the rig.[50] [52]

Features [edit]

Every sailing transport has a sheet programme that is adjusted to the purpose of the vessel and the ability of the crew; each has a hull, rigging and masts to agree up the sails that employ the current of air to power the transport; the masts are supported by standing rigging and the sails are adjusted by running rigging.

Hull [edit]

Hull class lines, lengthwise and in cantankerous-section from a 1781 plan

Hull shapes for sailing ships evolved from existence relatively short and blunt to being longer and finer at the bow.[8] By the nineteenth century, ships were built with reference to a one-half model, made from wooden layers that were pinned together. Each layer could be scaled to the bodily size of the vessel in order to lay out its hull construction, starting with the keel and leading to the ship's ribs. The ribs were pieced together from curved elements, chosen futtocks and tied in place until the installation of the planking. Typically, planking was caulked with a tar-impregnated yarn fabricated from manila or hemp to make the planking watertight.[53] Starting in the mid-19th century, iron was used first for the hull structure and later for its watertight sheathing.[54]

Masts [edit]

Diagram of rigging on a square-rigged ship.[55]

Until the mid-19th century all vessels' masts were made of wood formed from a single or several pieces of timber which typically consisted of the trunk of a conifer tree. From the 16th century, vessels were oft built of a size requiring masts taller and thicker than could exist made from single tree trunks. On these larger vessels, to achieve the required height, the masts were built from up to four sections (also called masts), known in order of ascent height to a higher place the decks equally the lower, top, topgallant and royal masts.[56] Giving the lower sections sufficient thickness necessitated building them upwardly from separate pieces of wood. Such a department was known as a made mast, as opposed to sections formed from single pieces of timber, which were known as pole masts.[57] Starting in the 2nd one-half of the 19th century, masts were made of iron or steel.[8]

For ships with square sails the principal masts, given their standard names in bow to stern (front to back) order, are:

- Fore-mast – the mast nearest the bow, or the mast forward of the main-mast with sections: fore-mast lower, fore topmast, and fore topgallant mast[56]

- Main-mast – the tallest mast, usually located near the middle of the ship with sections: main-mast lower, main topmast, primary topgallant mast, royal mast (sometimes)[56]

- Mizzen-mast – the aft-most mast. Typically shorter than the fore-mast with sections: mizzen-mast lower, mizzen topmast, and mizzen topgallant mast.[58]

Sails [edit]

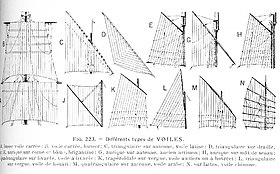

Unlike sail types.[59]

Each rig is configured in a sail plan, appropriate to the size of the sailing craft. Both square-rigged and fore-and-aft rigged vessels have been built with a wide range of configurations for single and multiple masts.[60]

Types of sail that can be office of a canvas plan can be broadly classed by how they are fastened to the sailing craft:

- To a stay – Sails attached to stays, include jibs, which are attached to forestays and staysails, which are mounted on other stays (typically wire cablevision) that support other masts from the bow aft.

- To a mast – Fore-and-aft sails directly fastened to the mast at the luff include gaff-rigged quadrilateral and Bermuda triangular sails.

- To a spar – Sails fastened to a spar include both square sails and such fore-and-aft quadrilateral sails every bit lug rigs, junk and spritsails and such triangular sails equally the lateen, and the crab claw.

Rigging [edit]

Square canvass edges and corners (pinnacle). Running rigging (bottom).

Sailing ships have standing rigging to support the masts and running rigging to heighten the sails and control their ability to draw power from the wind. The running rigging has three main roles, to support the sheet structure, to shape the sail and to adjust its bending to the wind. Square-rigged vessels require more controlling lines than fore-and-aft rigged ones.

Standing rigging [edit]

Sailing ships prior to the mid-19th century used wood masts with hemp-cobweb standing rigging. Every bit rigs became taller by the end of the 19th century, masts relied more heavily on successive spars, stepped 1 atop the other to course the whole, from bottom to tiptop: the lower mast, acme mast, and topgallant mast. This construction relied heavily on back up by a complex array of stays and shrouds. Each stay in either the fore-and-aft or athwartships direction had a respective one in the reverse direction providing counter-tension. Fore-and-aft the system of tensioning started with the stays that were anchored in front each mast. Shrouds were tensioned by pairs deadeyes, circular blocks that had the large-bore line run around them, whilst multiple holes allowed smaller line—lanyard—to laissez passer multiple times between the 2 and thereby allow tensioning of the shroud. Afterwards the mid-19th century square-rigged vessels were equipped with iron wire standing rigging, which was superseded with steel wire in the tardily 19th century.[61] [40] : 46

Running rigging [edit]

Halyards, used to heighten and lower the yards, are the primary supporting lines.[62] In addition, square rigs have lines that elevator the sail or the 1000 from which it is suspended that include: brails, buntlines, lifts and leechlines. Bowlines and clew lines shape a square sail.[55] To adapt the angle of the sheet to wind braces are used to adapt the fore and aft bending of a m of a square sail, while sheets attach to the clews (bottom corners) of a sail to control the sail'due south angle to the wind. Sheets run aft, whereas tacks are used to haul the clew of a foursquare sail forward.[55]

Crew [edit]

Seamen aloft, shortening canvas

The crew of a sailing ship is divided between officers (the captain and his subordinates) and seamen or ordinary easily. An able seaman was expected to "hand, reef, and steer" (handle the lines and other equipment, reef the sails, and steer the vessel).[63] The crew is organized to stand up sentinel—the oversight of the ship for a period—typically four hours each.[64] Richard Henry Dana Jr. and Herman Melville each had personal experience aboard sailing vessels of the 19th century.

Merchant vessel [edit]

Dana described the crew of the merchant brig, Pilgrim, every bit comprising six to eight common sailors, four specialist crew members (the steward, melt, carpenter and sailmaker), and 3 officers: the helm, the showtime mate and the 2nd mate. He contrasted the American crew complement with that of other nations on whose similarly sized ships the crew might number as many as thirty.[65] Larger merchant vessels had larger crews.[66]

Warship [edit]

Melville described the crew complement of the frigate warship, U.s.a., as about 500—including officers, enlisted personnel and 50 Marines. The crew was divided into the starboard and larboard watches. It was also divided into 3 tops, bands of crew responsible for setting sails on the three masts; a ring of sail-anchor men, whose station was forward and whose job was to tend the fore-yard, anchors and forward sails; the subsequently guard, who were stationed aft and tended the mainsail, spanker and man the various sheets, controlling the position of the sails; the waisters, who were stationed midships and had menial duties attending the livestock, etc.; and the holders, who occupied the lower decks of the vessel and were responsible for the inner workings of the ship. He additionally named such positions as, boatswains, gunners, carpenters, coopers, painters, tinkers, stewards, cooks and various boys as functions on the man-of-war.[67] 18-19th century ships of the line had a complement equally high every bit 850.[68]

Ship handling [edit]

Sailing ship at body of water, rolling and heeled over from the force of the wind on its sails.

Handling a sailing ship requires direction of its sails to power—merely not overpower—the ship and navigation to guide the ship, both at sea and in and out of harbors.

Under sail [edit]

Fundamental elements of sailing a ship are setting the right amount of sheet to generate maximum power without endangering the ship, adjusting the sails to the wind direction on the course sailed, and changing tack to bring the wind from one side of the vessel to the other.

Setting sail [edit]

A sailing send crew manages the running rigging of each square sail. Each canvass has two sheets that control its lower corners, ii braces that control the bending of the yard, two clewlines, four buntlines and ii reef tackles. All these lines must be manned as the sail is deployed and the yard raised. They utilize a halyard to enhance each yard and its sail; and so they pull or ease the braces to set the angle of the yard beyond the vessel; they pull on sheets to haul lower corners of the canvas, clews, out to 1000 below. Nether fashion, the crew manages reef tackles, haul leeches, reef points, to manage the size and angle of the canvass; bowlines pull the leading edge of the sail (leech) taut when close hauled. When furling the sail, the crew uses clewlines, haul up the clews and buntlines to booty up the middle of sail upward; when lowered, lifts back up each thou.[69]

In stiff winds, the crew is directed to reduce the number of sails or, alternatively, the amount of each given canvass that is presented to the wind by a procedure chosen reefing. To pull the sail up, seamen on the yardarm pull on reef tackles, attached to reef cringles, to pull the sail up and secure it with lines, called reef points.[70] Dana spoke of the hardships of sail handling during high wind and rain or with ice covering the ship and its rigging.[65]

Changing tack [edit]

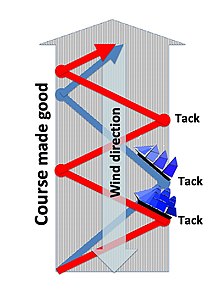

Diagram contrasting form fabricated skilful to windward by tacking a schooner versus a square-rigged send.

Sailing vessels cannot sail directly into the wind. Instead, square-riggers must sail a course that is between 60° and seventy° away from the wind management[71] and fore-and aft vessels can typically sail no closer than 45°.[72] To reach a destination, sailing vessels may take to change grade and permit the wind to come up from the opposite side in a process, chosen tacking, when the air current comes across the bow during the maneuver.

When tacking, a foursquare-rigged vessel'southward sails must be presented squarely to the wind and thus impede forward motion every bit they are swung around via the yardarms through the air current equally controlled by the vessel's running rigging, using braces—adjusting the fore and aft angle of each yardarm around the mast—and sheets attached to the clews (bottom corners) of each sail to control the sail'south angle to the wind.[55] The process is to turn the vessel into the wind with the hind-most fore-and-aft sail (the spanker), pulled to windward to assistance turn the ship through the eye of the wind. Once the transport has come near, all the sails are adapted to align properly with the new tack. Because square-rigger masts are more strongly braced from behind than from alee, tacking is a dangerous procedure in strong winds; the ship may lose forward momentum (become defenseless in stays) and the rigging may fail from the wind coming from ahead. The send may as well lose momentum at wind speeds of less than 10 knots (nineteen km/h).[71] Nether these conditions, the choice may be to wear transport—to turn the ship away from the air current and around 240° onto the next tack (60° off the current of air).[73] [74]

A fore-and-aft rig permits the wind to flow by the sail, as the craft head through the eye of the current of air. Most rigs pivot around a stay or the mast, while this occurs. For a jib, the old leeward sheet is released as the craft heads through the wind and the one-time windward sail is tightened as the new leeward sheet to let the sail to draw wind. Mainsails are ofttimes self-disposed and slide on a traveler to the opposite side.[75] On certain rigs, such as lateens[76] and luggers,[77] the sail may be partially lowered to bring it to the contrary side.

[edit]

The marine sextant is used to measure the elevation of celestial bodies above the horizon.

Early navigational techniques employed observations of the sun, stars, waves and birdlife. In the 15th century, the Chinese were using the magnetic compass to place management of travel. By the 16th century in Europe, navigational instruments included the quadrant, the astrolabe, cantankerous staff, dividers and compass. By the time of the Age of Exploration these tools were being used in combination with a log to measure out speed, a lead line to measure soundings, and a lookout to identify potential hazards. Later, an accurate marine sextant became standard for determining breadth and an authentic chronometer became standard for determining longitude.[78] [79]

Passage planning begins with laying out a route along a chart, which comprises a serial of courses between fixes—verifiable locations that confirm the bodily track of the ship on the body of water. Once a course has been ready, the person at the captain attempts to follow its management with reference to the compass. The navigator notes the fourth dimension and speed at each ready to approximate the arrival at the adjacent set, a process chosen expressionless reckoning. For coast-wise navigation, sightings from known landmarks or navigational aids may be used to found fixes, a procedure called pilotage.[1] At ocean, sailing ships used celestial navigation on a daily schedule, as follows:[80]

- Continuous dead reckoning plot

- Star observations at morning twilight for a celestial fix

- Morning lord's day ascertainment to determine compass mistake past azimuth observation of the sun

- Noontime observation of the sunday for noon breadth line for determination the day's run and mean solar day's set and drift

- Afternoon sunday line to determine compass error by azimuth observation of the dominicus

- Star observations at evening twilight for a celestial gear up

Fixes were taken with a marine sextant, which measures the distance of the celestial body above the horizon.[78]

Entering and leaving harbor [edit]

Given the limited maneuverability of sailing ships, it could be difficult to enter and leave harbor with the presence of a tide without analogous arrivals with a flooding tide and departures with an ebbing tide. In harbor, a sailing ship stood at anchor, unless it needed to exist loaded or unloaded at a dock or pier, in which case information technology might be warped alongside or towed by a tug. Warping involved using a long rope (the warp) between the ship and a fixed point on the shore. This was pulled on by a capstan on shore, or on the send. This might be a multi-stage process if the route was not simple. If no fixed point was available, a kedge anchor might be taken out in a ship's boat to a suitable indicate and the transport and then pulled upwardly to the kedge. Square rigged vessels could apply backing and filling (of the sails) to manoeuvre in a tideway, or control could be maintained by drudging the ballast - lower the anchor until information technology touches the bottom then that the dragging anchor gives steerage way in the catamenia of the tide.[81] [82] : 199–202

Examples [edit]

These are examples of sailing ships; some terms have multiple meanings:

| Defined by full general configuration

| Defined past canvas plan All masts have fore-and-aft sails

All masts have foursquare sails

Mixture of masts with foursquare sails and masts with fore-and-aft sails

Military vessels

|

Gallery [edit]

-

Götheborg, a sailing replica of a Swedish East Indiaman

-

USS Constitution with sails on display in 2012, the oldest commissioned warship however afloat[84]

-

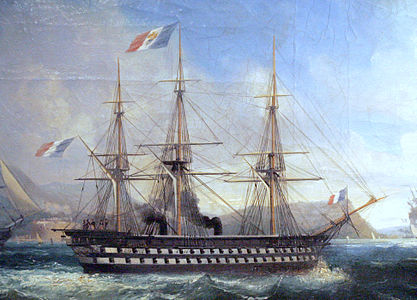

French steam-powered, screw-propelled battleship, Napoléon

Meet likewise [edit]

- Listing of large sailing vessels

- Sailboat

- Sailing transport accidents

- Sailing ship effect—describing the transition between an former and new applied science

- Sailing ship tactics

- Shipbuilding

- Tall transport

Notes [edit]

- ^ Freight: the cost paid for conveying a cargo

- ^ The fineness of a ship'southward hull is best described past considering a rectangular cuboid with the same length, breadth (beam) and depth as the hull of the transport. The more material that you have to cleave away to get the shape of the ship'due south hull, the finer the lines.

References [edit]

- ^ a b Quiller-Burrow, Arthur Thomas (1895). The Story of the Bounding main. Vol. 1. Cassell and Company. p. 760.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Square Riggers in the Usa and Canada, pp. 6–7, Transportation Trails, Polo, IL, 1994. ISBN 0-933449-19-4.

- ^ a b Meacham, Steve (eleven December 2008). "Austronesians were showtime to sail the seas". The Sydney Morning Herald . Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Bellina, Bérénice (2014). "Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road". In Guy, John (ed.). Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to eighth century. Yale University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN9781588395245.

- ^ "transport". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Printing. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Griffiths, Denis (1993). "Chapter five: Triple Expansion and the First Shipping Revolution". In Gardiner, Robert; Greenhill, Dr. Basil (eds.). The Advent of Steam - The Merchant Steamship before 1900. Conway Maritime Press Ltd. pp. 106–126. ISBN0-85177-563-2.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Robert J; Greenhill, Basil (1993). Canvas's Terminal Century : the Merchant Sailing Send 1830-1930. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN0-85177-565-ix.

- ^ a b c d e Anderson, Romola; Anderson, R. C. (2003-09-01). A Brusk History of the Sailing Transport. Courier Corporation. ISBN9780486429885.

- ^ Bonn-Muller, Eti. "First Minoan Shipwreck". Archæology Magazine. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 31 Baronial 2021.

- ^ a b Merson, John (1990). The Genius That Was China: East and W in the Making of the Modernistic World . Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press. ISBN978-0-87951-397-9.

- ^ Magnússon, Magnús (2016-10-06). The Vikings. Stroud [England]. p. xc. ISBN978-0750980777. OCLC 972948057.

- ^ Friedman, John Block; Figg, Kristen Mossler (2017-07-05). Routledge Revivals: Trade, Travel and Exploration in the Center Ages (2000): An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 322. ISBN9781351661324.

- ^ Norman, Vesey (2010). The Medieval Soldier. Pen and Sword. ISBN9781783031368.

- ^ Doran, Edwin, Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Gild. 83 (two): 130–140.

- ^ Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian gunkhole forms in the Indian Ocean". In Cringe, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archeology and Language Three: Artefacts languages, and texts. 1 World Archeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN978-0415100540.

- ^ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Commutation between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean Globe. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN9783319338224.

- ^ Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&Thou University Press. ISBN9780890961070.

- ^ a b Shaffer, Lynda Norene (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. 1000.E. Sharpe. Quoting Johnstone 1980: 191–192

- ^ Kang, Heejung (2015). "Kunlun and Kunlun Slaves as Buddhists in the Eyes of the Tang Chinese" (PDF). Kemanusiaan. 22 (1): 27–52.

- ^ Grice, Elizabeth (17 March 2004). "A foreign kind of dream come true". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Haddon, A.C. (1920). The Outriggers of Indonesian Canoes. London, Majestic Anthropological Institute of Groovy Uk and Republic of ireland.

- ^ a b c Paine, Lincoln (2013). The Body of water and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World. New York: Random House, LLC.

- ^ a b Worcester, G. R. Thousand. (1971). The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze. Naval Institute Press. ISBN0870213350.

- ^ Hall, Kenneth R. (2010-12-28). A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Merchandise and Societal Development, 100–1500. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 216. ISBN9780742567627.

- ^ Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Peradaban Maritim. Djakarta: Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN978-602-9346-00-8.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (2005). "The Zheng He Voyages: A Reassessment". Journal of the Malaysian Co-operative of the Royal Asiatic Society. 78 (one (288)): 37–58. JSTOR 41493537.

- ^ Gao, Emerge. "A Cursory History Of The Chinese Junk". Culture Trip . Retrieved 2019-06-02 .

- ^ Church, Sally K. (2005). "Zheng He: an investigation into the plausibility of 450-ft treasure ships". Monumenta Serica. 53: ane–43. doi:x.1179/mon.2005.53.one.001. JSTOR 40727457. S2CID 161434221.

- ^ Bulliet, Richard Due west.; Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Headrick, Daniel R.; Hirsch, Steven; Johnson, Lyman (2008). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History, Brief Edition, Book I: To 1550: A Global History. Cengage Learning. pp. 352–3. ISBN9780618992386.

- ^ Konstam, A. (2002). The History of Shipwrecks. New York: Lyons Printing. pp. 77–79. ISBN1-58574-620-7.

- ^ Block, Leo (2003). To Harness the Wind: A Brusk History of the Development of Sails. Naval Establish Printing. ISBN9781557502094.

- ^ Diffie, Bailey W.; Winius, George D. (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1850. Europe and the World in the Age of Expansion. Vol. i. p. 177. ISBN978-0-8166-0850-viii.

- ^ Potato, Patrick J.; Coye, Ray Due west. (2013). Wildcat and Its Compensation: Leadership Lessons from the Age of Discovery. Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-17028-3 . Retrieved 2019-06-23 .

- ^ Bergreen, Laurence (2003). Over the edge of the world : Magellan's terrifying circumnavigation of the earth (1st ed.). New York: Morrow. ISBN0066211735. OCLC 52047431.

- ^ Kingston, William H. One thousand. (2014-12-29). How Britannia came to Rule the Waves. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 123–82. ISBN9783845711935.

- ^ a b Lavery, Brian (2012). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Arrangement 1793–1815. Conway. ISBN9781844861750.

- ^ Gould, Richard A. (2011-04-29). Archaeology and the Social History of Ships. Cambridge University Printing. p. 216. ISBN9781139498166.

- ^ Winfield, Rif; Roberts, Stephen Due south. (2017). French Warships in the Age of Canvas 1626–1786. Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN9781473893535.

- ^ a b c MacGregor, David R (1993). British and American Clippers: A Comparing of their Design, Construction and Performance. London: Conway Maritime Press Limited. ISBN0 85177 588 8.

- ^ a b MacGregor, David R. (1983). The Tea Clippers, Their History and Evolution 1833-1875. Conway Maritime Press Limited. ISBN0-85177-256-0.

- ^ McKee, A. in Bass (ed.) 1972, p.235

- ^ Telegdi, J.; Trif, L.; Romanski, L. (2016). Montemor, Maria Fatima (ed.). Smart anti-biofouling composite coatings for naval applications. Smart composite coatings and membranes : transport, structural, environmental and free energy applications. Cambridge, Britain: Elsevier. pp. 130–one. ISBN9781782422952. OCLC 928714218.

- ^ Hay (May 15, 1863). On copper and other capsule. The Engineer. London: Office for Publication and Advertisements. p. 276.

- ^ a b Mccarthy, Michael (2005). Ships' Fastenings: From Sewn Boat to Steamship. Texas A&M University Press. p. 131. ISBN9781603446211.

- ^ Knight, R. J. B. "The introduction of copper sheathing into the Royal Navy, 1779–1786" (PDF). rogerknight.org . Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ a b Schäuffelen, Otmar (2005). Chapman Great Sailing Ships of the World. Hearst Books. ISBN9781588163844.

- ^ Randier, Jean (1968). Men and Ships Around Cape Horn, 1616–1939. Barker. p. 338. ISBN9780213764760.

- ^ Cumming, Bill (2009). Gone – a chronicle of the seafarers & fabulous clipper ships of R & J Craig of Glasgow : Craig's "Counties". Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson. ISBN9781849270137. OCLC 491200437.

- ^ Sutherland, Jonathan; Canwell, Diane (2007-07-07). Container Ships and Oil Tankers. Gareth Stevens. ISBN9780836883770.

- ^ a b Staff (Apr xiii, 2009). "Sailing at the bear on of a button". Depression-Tech Magazine . Retrieved 2019-06-xx .

- ^ Chatterton, Edward Keble (1915). Sailing Ships and Their Story :the Story of Their Evolution from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Lippincott. pp. 298.

- ^ "Black Pearl". world wide web.boatinternational.com. Boat International Media Ltd. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ Staff (2012). "Designing and Building a Wooden Ship". Penobscot Marine Museum . Retrieved 2019-06-22 .

- ^ Clark, Arthur Hamilton (1912). The Clipper Ship Era: An Prototype of Famous American and British Clipper Ships, Their Owners, Builders, Commanders, and Crews, 1843–1869. G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- ^ a b c d Biddlecombe, George (1990). The Art of Rigging: Containing an Explanation of Terms and Phrases and the Progressive Method of Rigging Expressly Adapted for Sailing Ships. Dover Maritime Series. Courier Corporation. p. 13. ISBN9780486263434.

- ^ a b c Keegan, John (1989). The Price of Admiralty . New York: Viking. pp. 278. ISBN0-670-81416-four.

- ^ Fincham, John (1843). A Treatise on Masting Ships and Mast Making: Explaining Their Principles and Practical Operations, the Mode of Forming and Combining Made-masts, Etc. London: Whittaker. pp. 216–xxx.

- ^ Harland, John. Seamanship in the Age of Sail, pp. 15, 19–22, 36–37, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1992. ISBN 0-87021-955-iii.

- ^ Clerc-Rampal, K. (1913) Mer : la Mer Dans la Nature, la Mer et 50'Homme, Paris: Librairie Larousse, p. 213

- ^ Folkard, Henry Coleman (2012). Sailing Boats from Around the World: The Classic 1906 Treatise. Dover Maritime. Courier Corporation. p. 576. ISBN9780486311340.

- ^ zu Mondfeld, Wolfram (2005). Historic Transport Models. Sterling Publishing Visitor, Inc. p. 352. ISBN9781402721861.

- ^ Howard, Jim; Doane, Charles J. (2000). Handbook of Offshore Cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 468. ISBN9781574090932.

- ^ Editors. "Seamanship – Oxford Reference". www.oxfordreference.com. p. Seamanship. Retrieved 2019-06-24 .

- ^ Tony Grayness. "Workshop Hints: Ship's Bells". The British Horological Institute. Archived from the original on nine November 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ a b Dana, Richard Henry (1895). 2 Years Earlier the Mast: A Personal Narrative. Houghton, Mifflin. pp. xi–13.

- ^ Armstrong, John (2017-12-01). The Vital Spark: The British Littoral Merchandise, 1700–1930. Oxford University Printing. ISBN9781786948960.

- ^ Melville, Herman (1850). White-jacket; Or, The World in the Man-of-state of war. Harper. pp. fourteen–8.

- ^ Lavery, Brian (1983). The ship of the line. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN0851772528. OCLC 10361880.

- ^ Queeney, Tim (April 25, 2014). "Square sail handling – Bounding main Navigator – May/June 2014". www.oceannavigator.com . Retrieved 2019-06-23 .

- ^ Mayne, Richard (2000). The Linguistic communication of Sailing. New York: Routledge. pp. reef. ISBN9781135965655.

- ^ a b Editor (January 1, 2003). "Tall ship canvass handling – Ocean Navigator – January/February 2003". world wide web.oceannavigator.com . Retrieved 2019-06-23 .

- ^ Royce, Patrick One thousand. (1997). Royce's Sailing Illustrated. ProStar Publications. ISBN9780911284072.

- ^ Findlay, Gordon D. (2005). My Hand on the Tiller. AuthorHouse. p. 138. ISBN9781456793500.

- ^ Goodwin, Peter (2018-01-25). HMS Victory Pocket Transmission 1805: Admiral Nelson'southward Flagship At Trafalgar. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN9781472834072.

- ^ Jobson, Gary (2008). Sailing Fundamentals (Revised ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 224. ISBN978-1-4391-3678-2.

- ^ Campbell, I.C. (1995), "The Lateen Sail in Earth History" (PDF), Periodical of Globe History, vol. half-dozen, no. ane, pp. 1–23, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-04, retrieved 2017-06-16

- ^ Skeat, Walter W. (2013). An Etymological Dictionary of the English language Language. Dover language guides (Reprint ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 351. ISBN978-0-486-31765-6.

- ^ a b Johnston, Andrew Thousand.; Connor, Roger D.; Stephens, Carlene East.; Ceruzzi, Paul Due east. (2015-06-02). Time and Navigation: The Untold Story of Getting from Here to In that location. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN9781588344922.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 765–767.

- ^ Turpin, Edward A.; MacEwen, William A.; Hayler, William B. (1965). Merchant Marine officers' handbook. Cambridge, Doc.: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN087033056X. OCLC 228950964.

- ^ Whidden, John D. (1912). Ocean Life in the Old Sailing Ship Days: From Forecastle to Quarter-deck. Lilliputian, Dark-brown, & Co.

- ^ Harland, John (1984). Seamanship in the Age of Sail: an account of the shiphandling of the sailing homo-of-war 1600-1860, based on contemporary sources. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN978-1-8448-6309-nine.

- ^ "Cutty Sark". Royal Museums Greenwich Website . Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Square Riggers in the United States and Canada, p. 12, Transportation Trails, Polo, IL, 1994. ISBN 0-933449-nineteen-iv.

Farther reading [edit]

- Graham, Gerald South. "The Ascendancy of the Sailing Ship 1850-85." Economical History Review, 9#i 1956, pp. 74–88 online

- Watts, Philip (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 880–970, run into pages 881 to 887.

I. History to the Invention of Steamships

External links [edit]

![]() Media related to Sailing ships at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sailing ships at Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sailing_ship

Posted by: davisbronge1978.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Sailors Repair Sails In 1906"

Post a Comment